Coursework_California College of the Arts_MArch_Spring 2016

Instructor_Brian Price

A Mannerist Aura

“We can have words without a world but no world without words… (Goodman 6).” World-making is a language. It is a communication between form and subject, and as new worlds are sought to be made, as architecture seeks emancipation from bygone worlds of antiquity, the dialectic of the worlds of man and form is most imperative. While more extreme architectural form, such as Giulio Romano’s Palazzo del Ti and Peter Eisenman’s houses can easily prove the communicative effects of form and an individual’s world, here I am more interested in the minute techniques that define the worlds of a modest Midwestern church—the form and subject of which has seldom been discussed as providing such emancipation and world-making. However, Eliel Saarinen’s mannerisms at the First Christian Church in Columbus, Indiana—as he navigates a discussion between the worlds of holy righteousness in sacred form and the contrite worship of the Christian congregation—offers the potential of a new insight into a critical practice of architecture.

The Auras of Man and Form

In his book “Search for Form,” Saarinen sought to analyze the potential for emancipation of the arts and architecture from the classical styles in the 1940s. He writes, “Life has run its normal course, but in many respects the employed forms breathe the alien spirit of a distant past. Our rooms, homes, buildings, towns, and cities have become the innocent victims of miscellaneous styles, accumulated from the abundant remnants of earlier epochs (Saarinen 1).” Here he finds the current moment in a transition of worlds. On one side the bygone world of ancient form, and on the other the emerging world of modern man, but this divide has not happened autonomously. Saarinen writes, “Form is something which is in man, which grows when man grows, and which declines when man declines (3).” We see that the correlation of these worlds, of form and of man, has a direct relationship. As one world impresses itself the other reacts, for better or worse. Thus, to search for this new architecture of the current moment, Saarinen unpacks the relationship of where these worlds collide, that is the relationship of man and form’s respective “auras”.

Saarinen asks, “’What is arts?’ the answer, as said, must be found in man himself.” As we concern ourselves with the issues of man, we can see man as a “matter of form.” That is, that man exudes influence just as does form. And, “the spiritual essence that radiates from an individual is called ‘aura’ (Saarinen 125).” We can further understand what Saarinen calls the aura of man as one’s personality or individuality, and when two individualities mingle, one is “confronted with an appearance consisting of proportions, masses, rhythm, color, and movement (126).” This is the relationship of man to form. He continues that when a person “creates, understands, or appreciates art, [he/she] is subconsciously bound to do it in accordance with that ‘individuality’ he represents… in other words, an individual transposes his ”aura of man” into his “aura of form (125-126).”

Now then, we turn our attention to the “Aura of Form” where “the spiritual quality of a form rests within its expressive proportion and rhythm.” As Saarinen features, the room is an architectural form that defines the “sanctuary of man’s life and work,” and it “is that environment, constituted by means of proportion and rhythm, which bestows upon man its spiritual atmosphere (Saarinen 127).” And as such, does not the aura of form and man contain comparative qualities? They relate by tangible means. Man exudes a value that affects the world of form, and form emanates a charge that affects the world of man. With this knowledge then, one can analyze the ambitions of Saarinen’s new form as navigating between the worlds of man and form; and here we come to the dynamic worlds of the First Christian Church—a space where opposing auras of sacred form and afflicted man collide.

The world of man as Christian worshiper is plagued by sin and guilt. As one Psalmist sings out in prayer, “my soul is full of troubles, and my life draws near to [the grave]. I am counted among those who go down to the pit; I am a man who has no strength, like one set loose among the dead, like the slain that lie in the grave, like those whom you remember no more, for they are cut off from your hand (ESV, Psalms 88:3-5).” Here lay the aura of man, separated from God and left for the grave.

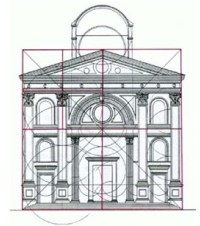

The world of holy form, however, is traditionally one of transcendent and sovereign aura in proportion and rhythm—a form for the residence of God—as was endeavored by Leon Battista Alberti’s perfection of proportion at the Basilica of Sant’Andrea di Mantova. Here the aura of form is as John Summerson describes in his book “The Classical Language of Architecture” that, “the aim of classical architecture has always been to achieve a demonstrable harmony of parts (Summerson 8),” which “can only be secured if the shapes of rooms and openings in walls and indeed all elements in a building are made to conform with certain ratios which are related continuously to all other ratios in the building (45).” At Sant’Andrea, Alberti’s organization of the geometries of entry flanked by pairs of ordered columns and intermittent arches that all graciously support the pediment above holds fast to the systematic proportions and symmetry outlined by subdivisions of the overall square façade. This is the logical, spiritual technique of orderly form that emits a righteous aura worthy of its sacred world.

Mannerisms and Aura

And here I will turn attention toward architectural technique, specifically that of the First Christian Church, as it holds the capacity to navigate and manipulate these two worlds, and of which we can understand within the guise of Mannerism. According to Colin Rowe, from his article “Mannerism and Modern Architecture,” there is an inevitable yearning in the aura of man to oppose perfection, and that yearning is at the core of Mannerist performance. He writes, “An unavoidable state of mind, and not a mere desire to break rules, sixteenth century Mannerism appears to consist in the deliberate inversion of the classical High Renaissance norm as established by Bramante, to include the very human desire to impair perfection when once it has been achieved; and to represent, too, a collapse of confidence in the theoretical programmes of the earlier Renaissance (Rowe 292).” In Rowe’s latter catalyst of Mannerist architecture, we can easily place the camp of Eliel Saarinen. As explained previously, his objectives of dismantling the classical styles are clear as a collapse of confidence in their modern relevance. Rowe’s former facilitator of mannerisms, however, digs deeper to the aura of man and form that I am here analyzing. That is, that man’s aura contains the aptitude to overcome the perfections of form and cries out for emancipation from its flawlessness.

Rowe then continues by exposing a series of Mannerist patterns in modern architecture including structure, material, detail, and scale, as they depart from a referential framework; and his breakdown provides the foundation for a critical reading of Saarinen’s techniques at the First Christian Church and their correlation to the dialogue of worlds between man and form. Rowe writes of modern Mannerism that, “it is essentially dependent on the awareness of a pre-existing order: as an attitude of dissent, it demands an orthodoxy within whose framework it might be heretical. Clearly… it becomes essential to find for it some corresponding frame of reference, some pedigree, within which it might occupy an analogous position (Rowe 292).” And he adds, “The Mannerist architect, working with the classical system, inverts the natural logic of its implied structural function; modern architecture makes no overt reference to the classical system. In more general terms the Mannerist architect works towards the visual elimination of the idea of mass, the denial of the ideas of load, or apparent stability. He exploits contradictory elements in a façade, employs harshly rectilinear forms, and emphasizes a type of arrested movement (298).” In alignment with Rowe’s description, and in opposition to Alberti’s deployment of stability between columns, arches and the pediment, Saarinen removes any classical reference of structure in his façade.  While the frame of reference at Saarinen’s First Christian Church is not one of Greek orders or any detail of the classical language, we can instead recognize a similar technique to Alberti’s proportions at the basilica. The representation of systematically subdivided geometries provides Saarinen a framework for departure. Upon the entrance façade, limestone panels portion the vertical plane into equally segmented rectangles, defining the rule for engagement of this surface. Here we witness the aura of sacred form among the impeccable display of proportion and rhythm of the grid. However, something is off as the corresponding elements do not conform to the determined ratios of the façade. Saarinen initiates the infiltration of man’s aura upon the form. The entrance opening is asymmetrically bracketed by three modules on one side and two on the other. Horizontally, the odd number of panels restricts the element from any hope of movement and residing in the center of the grid. One level of focus farther, the door panels within the opening have slid one unit to the side as they adjust to the cross above which has also mischievously been misaligned from any notion of a central axis.

While the frame of reference at Saarinen’s First Christian Church is not one of Greek orders or any detail of the classical language, we can instead recognize a similar technique to Alberti’s proportions at the basilica. The representation of systematically subdivided geometries provides Saarinen a framework for departure. Upon the entrance façade, limestone panels portion the vertical plane into equally segmented rectangles, defining the rule for engagement of this surface. Here we witness the aura of sacred form among the impeccable display of proportion and rhythm of the grid. However, something is off as the corresponding elements do not conform to the determined ratios of the façade. Saarinen initiates the infiltration of man’s aura upon the form. The entrance opening is asymmetrically bracketed by three modules on one side and two on the other. Horizontally, the odd number of panels restricts the element from any hope of movement and residing in the center of the grid. One level of focus farther, the door panels within the opening have slid one unit to the side as they adjust to the cross above which has also mischievously been misaligned from any notion of a central axis.  The door handles even exude this departure from the frame as they align just off center of the four-wide texture of wood strips beneath. To the west of the entrance, the spire is concerned in a similar dialogue. One surface is again defined as orthodox, pristine form by the grid of relief in the brick, while around the corner a clock slips from its expected location at the center of the plane, appearing to nearly fall from the top of the tower.

The door handles even exude this departure from the frame as they align just off center of the four-wide texture of wood strips beneath. To the west of the entrance, the spire is concerned in a similar dialogue. One surface is again defined as orthodox, pristine form by the grid of relief in the brick, while around the corner a clock slips from its expected location at the center of the plane, appearing to nearly fall from the top of the tower.

Inside the sanctuary, the vast, pure rectangular volume is unimpeded and outlines the frame of reference within the interior. Immediately the worshiper’s focus is dislocated by the misplacement of the cross above the pulpit in relation to its position within the sanctuary’s volume.  While the similar techniques of asymmetry applied to the exterior are intriguing, here altering the most spiritually significant architectural detail causes the viewer to ask, “Why?” The mannerism engages the worshiper’s participation in the consideration of heavenly form and orchestrates an interaction of man and form’s aura. And, from this communication of worlds a new openness develops within the reading of the sacred and the afflicted within the sanctuary.

While the similar techniques of asymmetry applied to the exterior are intriguing, here altering the most spiritually significant architectural detail causes the viewer to ask, “Why?” The mannerism engages the worshiper’s participation in the consideration of heavenly form and orchestrates an interaction of man and form’s aura. And, from this communication of worlds a new openness develops within the reading of the sacred and the afflicted within the sanctuary.  After the initial visual contact with the room, the malfunctions of the plan become apparent. The center aisle also does not align to the form’s impression of a proper axis while the two perimeter aisles render absurdly out of proportion—both moves of which inebriate the processional to and from the Alter. Saarinen even embeds a misrepresentation of sacred form in the structure of the sanctuary. The east colonnade has compressed to the human scale—a humble gesture, as traditionally it would define a glorious, monumental frame to the space. Opposite, the west colonnade does manifest as monumental, but merely by means of light, both natural and artificial, and denies the satisfaction of physical engagement by the spectator. Again and again, man and form’s aura collide at Saarinen’s First Christian Church amidst the employment of calculated mannerisms.

After the initial visual contact with the room, the malfunctions of the plan become apparent. The center aisle also does not align to the form’s impression of a proper axis while the two perimeter aisles render absurdly out of proportion—both moves of which inebriate the processional to and from the Alter. Saarinen even embeds a misrepresentation of sacred form in the structure of the sanctuary. The east colonnade has compressed to the human scale—a humble gesture, as traditionally it would define a glorious, monumental frame to the space. Opposite, the west colonnade does manifest as monumental, but merely by means of light, both natural and artificial, and denies the satisfaction of physical engagement by the spectator. Again and again, man and form’s aura collide at Saarinen’s First Christian Church amidst the employment of calculated mannerisms.

Lastly in analysis of the church, we must acknowledge the material qualities of such a project as Rowe points out, “In the choice of texture, surface and detail, aims general to Mannerism can also be detected. The surface of the Mannerist wall is either primitive or over-refined, and a brutally direct rustication frequently occurs in combination with and excess of attenuated and rigid delicacy (Rowe 298-289).” The limestone panels within the brick façade of the entrance is clearly representative of Rowe’s description of rustication, and serves as a motion respectful of man’s physical impedance upon the form. A reinforcement of the righteous aura of the form is then accomplished by the homogeneous application of exterior brick, and interior white paint.

So what then can be made of the Mannerist techniques and knowledge of auras and worlds as seen in Saarinen’s First Christian Church? I propose that we have here a new understanding of the rules for employing the Mannerist project. That is, that the relationship of worlds between man and form, when paired appropriately, or rather inappropriately, can inform the Mannerist technique. In the past, such technique was applied against the backdrop of an architectural canon. As we seek emancipation and criticality today within a void of any known canon, here lay a potential catalyst in worlds and auras and man and form.

Images

01 – Basilica Sant’Andrea di Mantova, Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472)

02 – First Christian Church (1940), Photo by Hedrich-Blessing

03 – Entrance door handle detail.

04 – First Christian Church Sanctuary Interior, Photo by Ben Martorell

05 – First Christian Church Sanctuary Plan

Work Cited

Goodman, Nelson. “Words, Works, Worlds.” Ways of Worldmaking. Indianapolis: Hackett Pub., 1978. Print.

Rowe, Colin. “Mannerism and Modern Architecture.” Architectural ReviewMay 1950: 289-99. Web.

Saarinen, Eliel. Search for Form; a Fundamental Approach to Art. New York: Reinhold Pub., 1948. Print.

Summerson, John. The Classical Language of Architecture. Cambridge: M.I.T., 1966. Print.