Coursework_California College of the Arts_Spring 2017

Instructor_Irene Cheng

Learning From Whiteness

“…architecture and the visual world always belong to and circulate within-indeed construct-the political, economic, and social worlds in which we live. Architecture is not benign, even (and sometimes especially) when it is spectacularly beautiful or when it is so ordinary we hardly notice it. And architecture is about race even (and perhaps especially) when it is situated in an all-white suburb-a fact that architectural historians have tended to overlook completely.”1

–Dianne Harris, Little White Houses

As we navigate the social worlds of today and consider a reoriented awareness of what it means to live in racially divided America, the question of architecture’s agency to engage those worlds has returned in parallel with the rebirth of interest in designers of the 1960’s and 70’s. Most notably, and the focus of this essay, is the “ordinary,” semiotic, mannerist works of Venturi and Scott Brown and their methods of breaking convention while “Learning From” the conventional. It seems appropriate that interest in this body of work, which gained prominence during the time of the first Civil Rights movement, has come again at a time of hard consideration of America’s racial history and its percolation into today’s society; and as we learn from those socio-political histories, we have an opportunity to learn anew from the architectural histories of our current interests through a lens of racial formation. The ambition for this research and writing is not an attempt at redefining the work of Venturi and Scott Brown as a racial project, but rather to learn from their interests around suburbia and the use of mannerisms in architecture as a process of uncovering a relevant critical strategy for architectural design in today’s racial climate.

Jonathan Massey, in his recent article titled “Power and Privilege” in which he reflects on the fiftieth anniversary of Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture critiques twentieth century mannerism as a “reinscription of privilege, a strategy through which elites renew the devalued currency of their cultural capital,” and that those elites were, “perhaps inadvertently—shoring up the value of a particular Anglo-American lineage of architectural academicism in order to protect its contemporary legatees.” He responds to this concern by then asking the question, “How can we intersect Venturi’s compositional and stylistic approach with analytics that reveal other kinds of architectural complexities and contradictions, such as those relating to architecture’s imbrications with systems of class and labor, gender and sexuality, ethnicity and race?”2 In response to this question, this essay proposes a return to Levittown and the lessons that Venturi and Scott Brown learned from analyzing the symbolic architectural styles that defined the domestic identities of a middle-class racially privileged community. Where Venturi and Scott Brown’s mannerisms engage with the languages of these communities, rather than the languages of the architectural elite, their delivery is more approachable to the general public and certainly more potent as a potential social activism. Filtered through the lens of Dianne Harris’ book Little White Houses these architectural symbols and signs of identity can be understood as a racial formation of “Whiteness” in the construction of post-war suburban America that flourished subconsciously in parallel to explicitly racist legislation and banking tactics. Considering the power of architectural symbolism as a subliminal formation of privilege and whiteness, a new conceptualization of mannerist techniques can be made as an architectural strategy for challenging hidden power structures by way of critical, vulgar magnification and manipulation of the systems at hand. This technique is then proposed as an internal working that confronts and challenges the undercurrents of racial privilege from within the hegemony of the architectural symbolisms and styles that proliferate the supremacy of white identities.

Constructing Post-War Whiteness

In order to analyze the symbolism and identity that Harris attributes to whiteness in the post-war suburban home, we must first lay a foundation for the greater political formation of whiteness in post-WII America. Policies for segregating property ownership were primarily choreographed by government agencies including the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) and the Veterans Administration (VA). Together the FHA and HOLC applied “a policy of ‘minority containment’” by “refusing to insure mortgage loans to any but white Americans.”3 Written into the mortgage agreement documentation, explicitly racist terms excluded non-whites from owning or residing permanently within the property. The intention of these redlining procedures was to minimize difference within American communities as a pursuit for comfort and wellbeing and was generally enacted “using justifications related to market and developer demands.”4 Harris states that, “as a result, between 1932 and 1964 the FHA and the [VA], through the GI Bill, ‘financed more than $120 billion forth of new housing, but less than 2% of this real estate was available to nonwhite families, and most of that small amount was located in segregated areas.”5

The implementation of these racist financial restrictions then folded into the physical and visual development of the American domestic fabric as expenditures on new construction. They were focused primarily on the cheap, rapid developments of suburban sprawl and paralleled efforts for urban renewal and slum clearances within American cities. In suburbia the FHA favored “traditional house types and forms” motivated by budget efficiencies and “anyone who wished to build less conventional homes quickly discovered that the FHA refused to provide mortgage insurance for their loans, since untested house types and forms were deemed high-risk investments.” Harris observes here that, “the FHA frowned on difference of any kind, whether in house form and style or in the identities of houses’ occupants.”6

These pervasive constructions of homogenous identities in suburbia by financial and political means were also reinforced symbolically through advertisements and public imagery. While the efforts toward inner city housing developments published the visual intensities of poverty in urban America—almost exclusively depictive of majority African American communities—the FHA used coded language in the media to validate the categorizing of racial identity through economic and social means. Harris delivers an explicit example here to expose the popular vision that, “black residential life included multigenerational and mixed-gender sleeping arrangements and social activities carried out on the front stoop, in the street, and in the alley instead of inside the private home or in the private backyard. Deteriorating and ramshackle construction marked by unglazed window openings, furnishings assembled from salvage sites, and unkempt surroundings might complete a stereotypical and essentializing image of black domestic life. It was an image white Americans experienced in sections of nineteenth-century cities; it was what they saw and read about in New Deal photographs of urban poverty.”7 These images then emerged via language that defined white communities in opposition. “Homogenous neighborhoods were called ‘secure’ or stable’ and were noted for possessing ‘integrity’,” and were defined by other racially coded rhetoric that “included ‘culture,’ ‘crime,’ ‘school quality,’ ‘property values,’ and ‘private’.”8 Divergent languages such as “clean/dirty, spacious/crowded, private/public, tidy/cluttered” then covertly defined the nature of white/black identities through a veil of domestic and societal symbolism, and can be seen in the media efforts of the time. Harris specifically points out that, “terms such as privacy, ease, luxury, freedom, informality, order, cleanliness, and spaciousness (among others) appeared consistently in the sales and advertising literature—in print and on television—related to post-war house design and decoration.”9 In relation to the stigma of urban blight, this language that defines an idyllic image of suburban domesticity can then be understood as structuring a picturesque identity of whiteness in post-war America, and is particularly at play in the visual and stylistic symbolism of the suburban housing market.

Meaning and Symbolism of Style in the American Suburban Home

Considering the symbolic nature of the post-war suburban housing style that Dianne Harris explains as crucial in the formation of white American identities, a new examination can be made of Venturi and Scott Brown’s practice on architectural style and suburban conditions. In Denise Scott Brown’s article for Oppositions 5 titled “On Architectural Formalism and Social Concern,” she “calls for a theory of form and meaning in architecture.”10 In defense of style, Scott Brown declares that “formal languages have always been a part of architecture…[and] that even the early Moderns, after they had cast out the styles and the orders and thought they were free and clear, shared a formal language… that made the International Style recognizably a style.”11 She continues that, “those who refuse to study form and the vocabularies and grammar of formal languages because they believe form should be a mere resultant of other considerations, tend to find themselves the prisoners of irrelevant formal hand-me-downs whose tyranny is more severe for being unadmitted.”12 Referring here to the ideals of functionalist Modernism that was deployed in urban renewal projects such as Pruitt-Igoe and Cabrini Green, Scott Brown advocates for a revitalized concern for style in architecture and in response turns to suburbia as an exemplar of culturally relevant architectural formalism. Scott Brown, along with her partners Robert Venturi and Steve Izenour explained in an article titled “The Home” that “We focused primarily upon the 20th century commercial strip and suburban sprawl because in these environments the tradition of using symbolism in architecture has continued from the 19th century city, whereas in areas more directly controlled by architects that tradition was broken by Modern architects’ attempts to eradicate historical and symbolic association and decoration from architecture.”13

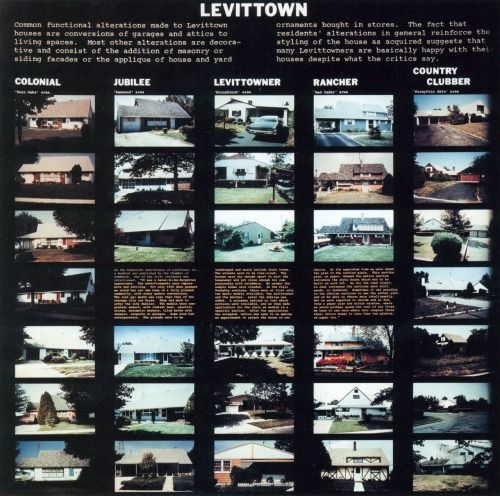

In their well-known study of the commercial strip documented in Learning from Las Vegas Scott Brown, Venturi and Izenour examined the visual culture and style of commercial America, appropriating the rigorous methodology akin to studying the architecturally “higher” conditions of classical European cities such as Rome. This controversial research uncovered a stylistic language of American architecture that proliferated meaning and symbolism through signage to define a social value of identity and expression. The lessons learned in Las Vegas were then applied to the housing environment of suburban America in a subsequent study titled “Learning from Levittown” which culminated in an exhibition titled “Signs of Life: Symbols in the American City,” both of which catalogued the imagery of suburban homes such as front lawn ornamentation, façade treatments, interior furnishings, and back yard landscaping as symbolic representations that bear significant meaning on the identity of the residents. From the exhibition Scott Brown, Venturi, and Izenour state that, “the physical elements of suburbia – the roads, houses, roof, lawns, and front doors – serve practical purposes such as giving access and shelter, but they also serve as a means of self-expression for suburban residents… The communication is mainly about social status, social aspirations, personal identity, individual freedom, and nostalgia for another time and place.”14

The efforts of the Levittown studio certainly suggest awareness to the racial struggles of the suburban community—“which was restricted to whites until August 1957”15 —although the issue has not typically been addressed in relation to the work. Jessica Lautin, in her article titled “More Than Ticky Tacky,” however references Venturi and Scott Brown and their position on researching suburban housing asserting that, “One could turn an unbiased, analytic eye to popular culture and suburbia without simultaneously supporting war, racism, poverty, or the subjugation of women.”16 The extent of racial engagement in the design portion of the studio came from one student in particular, Bob Miller, through a humorous appropriation of the Black Panther party. Miller’s design, an enlarged ranch style home fit to accommodate multiple families of diverse racial and economic status, was modeled architecturally as a cake and was eaten by the attending reviewers and class mates. The project was titled “Panther Arms” as Miller “supplanted the black-faced lawn jockey often seen on suburban lawns with a Black Panther member—colored with red food dye—raising his fist in the party’s “Black Power” salute. The statue made a powerful symbolic statement—replacing a racist, elitist image, with one of radical race pride.”17 Bob Miller’s humor was certainly not universally accepted by the reviewers as a culturally acceptable strategy and is judiciously critiqued by Lautin as having “trivialized African Americans’ protests against both inadequate and inferior housing and residential segregation”18 by rendering the Black Panther as frosting on a cake. The broader example, however, of working within the ruleset of symbolic styles (the lawn ornamentation) to undermine and even reverse the narrative of racism, elitism, or privilege represented by those symbols provides a valuable potential for a mannerist project that pursues racial activism.

Considering the racial awareness of the Levittown studio in the context of researching suburbia during the height of the Civil Rights Movement, the pairing of Dianne Harris’ position on the formation of whiteness in suburban America—a construction contributed to by the deployment of symbolic languages of architectural style—opens the potential for a new reading of Venturi and Scott Brown’s architectural practice. The intersection of these two lineages of suburban study begs the questions, “how can Venturi and Scott Brown’s housing designs be understood in the context of American whiteness,” “what new readings can emerge from their architecture through this cross examination,” and “how would such an analysis inform an architectural practice that is relevant in addressing today’s cultural and racial climate? In order to make such an analysis, Venturi and Scott Brown’s vested interest in the deployment of mannerisms as a methodology for social engagement can provide a critical edge to these questions.

Mannerisms of Venturi and Scott Brown

In the book Architecture as Signs and Systems: For a Mannerist Time, Robert Venturi defines Mannerism “as acknowledging a conventional order that is then modified or broken to accommodate valid exceptions.”19 This method of breaking convention has been recognized in architecture back to the sixteenth century work of Guilio Romano and his attacks on the High Renaissance styles and has been traced through many prominent architectural histories of style and order as a process for dismantling the predominant assumptions of architecture as emancipation from their hegemony. Colin Rowe, in his essay “Mannerism and Modern Architecture” even attributes mannerist working to early Modern architects such as Le Corbusier in their pursuit to overcome the neo Classical languages.

Venturi’s vision of mannerist architecture is in its potential to accommodate an increasingly pluralistic world rather than in pursuing a purification of it, and is detailed in his “gentle manifesto” Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture. Denise Scott Brown suggests that “Complexity and Contradiction could also be seen as an early salvo of [active] socioplastics,”20 —a term borrowed from Alison and Peter Smithson that labels their methods to “canvas the street life… for ideas on how to design housing.”21 She continues that “while writing it in 1962 and 1963, Bob was practicing architecture and teaching at Penn. He was also reverberating to the civil rights movement and the social planning furor at Penn. He was in contact with my urban design studios, …and saw the photographs I was taking of street signs and the retail environment.,” and had other influences which “included his socialist, pacifist mother… and the criticism of his college friend Philip Finkelpearl, a scholar of literary mannerism.”22 This vantage point of Venturi’s writing is uncommon as many scholars have criticized the manifesto as having been removed from all relevant social issues of the time, yet it is an important one in considering the potential for social engagement in Venturi and Scott Brown’s architecture through a mannerist methodology.

In the opening of Complexity and Contradiction Venturi writes, “I like elements which are hybrid rather than ‘pure,’ compromising rather than ‘clean,’ distorted rather than ‘straightforward,’ ambiguous rather than ‘articulated,’ perverse as well as impersonal, boring as well as ‘interesting,’ conventional rather than ‘designed,’ accommodating rather than excluding, redundant rather than simple, vestigial as well as innovating, inconsistent and equivocal rather than direct and clear. I am for messy vitality over obvious unity. I include the non-sequitur and proclaim the duality.”23 Venturi’s interests in mannerism here formulate a polemic against the purity, cleanliness and picturesqueness that was pervasive in the Modernist abolition of architectural style and can be folded back into the narrative of meaning and symbolism found in the styles of American suburban housing. Where Venturi and Scott Brown were canvassing the commercial strip in Las Vegas and the housing stock of Levittown for a wealth of architectural meaning and style, they also catalogued a series of contradictions within the languages of suburban style that both prescribe to and deviate from the conventions of privacy, cleanliness, spaciousness and tidiness.

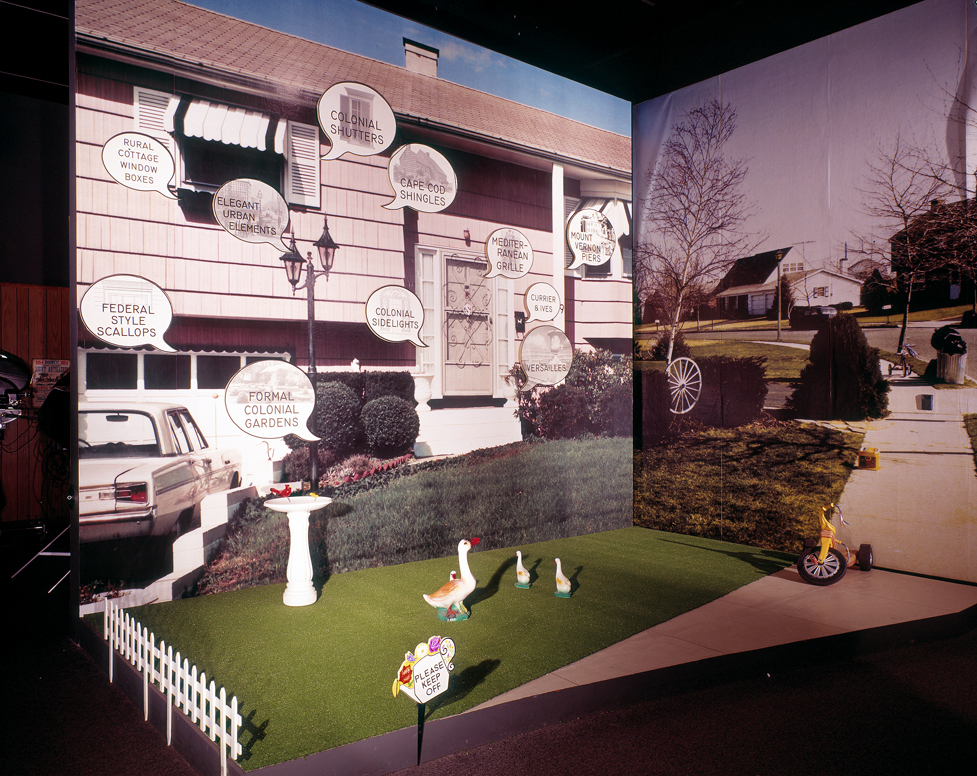

Close analysis of the photographs taken of Venturi and Scott Brown’s Signs of Life exhibition at the Renwick Gallery in 1976—where they annotate the symbolic elements of the façade and interior styles found in Levittown—exposes the contradictions that define the identities of suburban housing. On the exterior the finely manicured lawn is restricted to walking on by a sign that reads “Please Keep Off”, yet it is decorated by ceramic lawn ornaments of geese and is surrounded by the abandoned mess of children’s toys. “Formal Colonial Gardens” are precisely manicured yet accompanied by an “Elegant Urban” lamp post. Colonial elements such as shutters, sidelights contrast to rural styles of shingling and window planters. And the relentless privacy defined by the opacity of the façade and its indirect access through a barricaded driveway is almost broken by the restrained bay window that attempts even the slightest connection to the street. Inside the house is found a scattering of stylized furniture including an “Edwardian Club” chair, “Comfortable Chippendale” couch, and “Country Colonial” tables. Sneakily placed among this eclectic mix of ornamental furnishings sits a “Bauhaus Survival” lamp with its metallic industrial aesthetic as both in juxtaposition to and fitting collaboration with the style of the room. The backyard is then invited into the house by a large modern sliding door and exposes the multicultural exterior beyond. A “Japanese Garden” is overlaid by “Colonial Brick Paving” and decorated by “Regency Style” artifacts.

In Denise Scott Brown’s article “On Houses and Housing” she references the work of this exhibition and the Learning from Levittown studio as a body of research that “staked out the territory of symbolism in the home,” and “was an attempt to redefine what should be the totality of architects’ concerns with the architectural aspects of housing.”24 That is to say the identity of homeowners found in the symbolic styles that decorate their houses is an architectural project with regards to housing, and that these contradictions of style pose a language with which both architects and homeowners can engage.

Dismantling Symbolic Whiteness in the Suburban Home

Looking back at Venturi and Scott Brown’s earlier design work at the Vanna Venturi house, one can find traces of these languages and contradictions that define the identity of post-war suburban housing. While architects typically analyze the project in terms of its classical references and high-brown jokes against the Modernist elites, here an analysis is warranted in comparison and contradiction to the symbols of suburban whiteness as set forth by Diane Harris—namely the elements that promote the vocabulary of privacy, security, tidiness and spaciousness. Under this analysis the house is understood simultaneously as an ideal representation of the white suburban house and a vulgar critique of the same.

As a symbol of post-war suburbia, the front façade stands as a sign to the street. It is an architectural billboard to be read at face value for its mannerist references and contradictions. First, the gabled profile and vertical chimney signify that this is in fact a stand-alone, picturesque, single-family home. The profile however is oriented inappropriately to show the gabled face of the roof rather than the pitched face that is standard to the post-war façade. Here the “side” of the house is shown to the street and exposes what would typically be an imperfect and less orderly treatment of the exterior elements. While the “side” is brought to the front, the façade is still set back far from the property line and expressed as a heavy opaque surface to strongly delimit privacy from the street. On the façade a picture window is unfortunately located with regards to the proportion of the house. Dianne Harris notes that “the picture window became an icon of post-war domesticity” however she continues that it “prompted debates about the need for privacy in the home.”25 Here the oversized window on the Vanna Venturi house is a reinforcement of suburban values yet it bears the mannerist contradiction of identities as it opens a view into one bedroom and is perpetually covered by interior shades. Conversely, the opposite strip window must be broken and located messily across the symmetry of the façade to accommodate the interior plan. The entrance to Vanna Venturi’s house also expresses a contradiction that both challenges and subscribes to the post-war suburban identity. A poster from Venturi and Scott Brown’s Levittown research reads, “A symbol of hospitality and warmth, the front door is the first element for symbolic decoration.”26 The struggle between symbolic hospitality and extreme privacy is then apparent here as an opening is cut from the façade to provide a threshold across the overbearing front wall. The gesture is only a slight relief however as the front door is hidden from view within the shallow niche. Oppressive privacy is favored over a hospitable entry. Lastly, the symbolic value of tidiness to suburban whiteness is countered in both the graphic treatment of the façade and the landscaping. Trim molding is comically introduced to the façade in unorderly fashion and the green coloring of the exterior is offensive to the standard purity of white. Where the typical suburban home exterior is a rejection of its natural surrounding by maintaining a clean, white color, the desaturated green is more accepting of the dirty natural context. The yard however is perfectly manicured—a suburban requirement—with no plantings to obscure from the identity of the façade. One exception was originally made as a native tree once encroached onto the north corner of the house.

The interior likewise embodies similar strains of compliance to and contradiction against white suburban identity as postulated by Diane Harris. Large sliding doors, a staple of post-war housing, fracture the rear façade in a manner that struggles with the desired connection between interior and exterior. A stair is also introduced into the expectedly single story home and awkwardly compresses the spaciousness of the living space. It is consequently used as an extension of the mantle for displaying personal items and reflects the clutter that seems to frequent a well-trafficked domestic stair. Many eclectic artifacts then continue to clutter the interior yet are contradictorily embraced by extensive exposed shelving and specifically located open areas of wall and floor space intended to receive decorations and displays.

While Venturi and Scott Brown are primarily interested in dismantling the hegemony of Modernist architectural styles, a rereading of their work on suburban housing through the racialized lens of American suburbia posited by Dianne Harris, we can also observe a strategy for mannerist working on the visual controls of whiteness. In analyzing the well-known mannerisms of the Vanna Venturi house there are clearly short fallings if attempting to refer to the existing designed project as a racial one, however the analysis here is more productive in exposing the mannerisms that both contribute to the symbolic construction of post-war white identities as well as critique their meaning through exaggerated and abrasive manipulations. This conceptualization of deploying mannerisms then posits the potential for an architectural methodology that challenges the powerful undercurrents of our visual racial culture. Where the architectural images and stylistic expressions of ordinary post-war suburbia can be defined as a subconscious contribution to the supremacy of whiteness in America, mannerist operations can expose those subconscious systems in a shocking expression that confronts their hegemony from within.

Considering again Jonathan Massey’s question asking how we might overlay Venturi and Scott Brown’s mannerist methods of symbolism and style as an approach to engaging the marginalized systems of the world, this research proposes one consideration for leveraging the privileged technique of mannerisms as an antagonist to the privileged. Looking back to the Levittown studio and connecting Venturi and Scott Brown’s early mannerisms to the architectural symbols and styles that promulgated whiteness into post-war suburbia, several questions emerge for the viability and agency of this tactic. What assumptions of architectural style in today’s cultures are covertly continuing lineages of oppressive racial homogeneity? What new definition of mannerism can provide a subversive critique of those systems? And, how can an overtly activist mannerism reach beyond the privileged scale of architectural styles and begin to provoke broader realms of racism and prejudice across the world?

Notes:

- Dianne Suzette Harris, Little White Houses: How the Postwar Home Constructed Race in America (University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 3.

- Jonathan Massey, “Power and Privilege,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 75, no. 4 (2016): 498.

- Harris, Little White Houses, 34.

- Harris, Little White Houses, 34.

- Harris, Little White Houses, 34.

- Harris, Little White Houses, 35.

- Harris, Little White Houses, 38.

- Harris, Little White Houses, 37-38.

- Harris, Little White Houses, 43.

- Denise Scott Brown, “On Architectural Formalism & Social Concern,” Oppositions 5, (1976): 317.

- Scott Brown, “On Architectural Formalism”, 323.

- Scott Brown, “On Architectural Formalism”, 324.

- Robert Venturi, Steven Izenour and Denise Scott Brown, “The Home,” in On Houses and Housing (London : Academy Editions ; New York : St. Martin’s Press, 1992), 58.

- Venturi, Izenour and Scott Brown, “The Home”, 58.

- Harris, Little White Houses, 287.

- Jessica Lautin, “More Than Ticky Tacky: Venturi, Scott Brown, and Learning from the Levittown Studio” in Second Suburb : Levittown, Pennsylvania. edited by Dianne Harris (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania : University of Pittsburgh Press, 2010), 317.

- Lautin, “More Than Ticky Tacky,” 331-332.

- Lautin, “More Than Ticky Tacky,” 332.

- Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown, Architecture as Signs and Systems: for a Mannerist Time (Cambridge, Mass. : Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2004), 74.

- Denise Scott Brown, “Towards an Active Socioplastics,” in Having Words (London: AA Publications, 2010), 42.

- Scott Brown, “Towards an Active Socioplastics,” 25.

- Scott Brown, “Towards an Active Socioplastics,” 42.

- Robert Venturi, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (New York : Museum of Modern Art ; Boston : distributed by New York Graphic Society, 1977), 16.

- Denise Scott Brown, “On Houses and Housing,” in On Houses and Housing (London : Academy Editions ; New York : St. Martin’s Press, 1992), 10.

- Harris, Little White Houses, 113.

- Venturi, Izenour and Scott Brown, “The Home”, 63.

Images:

- USHA New Deal Poster

- National Homes Advertisement

- Learning from Levittown Research Poster

- Signs of Life House Exterior

- Sign of Life House Interior

- Advertisement for Post-War Block House

- Vanna Venturi House Front Elevation

- Vanna Venturi House Interior

Bibliography:

Bristol, Katharine G. “The Pruitt-Igoe Myth.” Journal of Architectural Education 44, no. 3 (1991): 163-71. doi:10.2307/1425266.

Butler, Christopher. Postmodernism a very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Fischer, Ole W. “Afterimage: A Comparative Rereading of Postmodernism.” Log, no. 21 (2011): 107-18. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41765405

Harris, Dianne Suzette. Little White Houses: How the Postwar Home Constructed Race in America. University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

Hooks, Bell. “Postmodern Blackness.” Postmodern Culture 1, no. 1 (1990).

Jencks, Charles A. The Language of Post-Modern Architecture. New York: Rizzoli, 1987.

Lautin, Jessica. “More Than Ticky Tacky: Venturi, Scott Brown, and Learning from the Levittown Studio” in Second Suburb : Levittown, Pennsylvania. edited by Dianne Harris, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania : University of Pittsburgh Press, 2010, 314-339

Massey, Jonathan. “Power and Privilege.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 75, no. 4 (2016): 497-498. doi: 10.1525/jsah.2016.75.4.497

Morton, Particia A. “The Legacy of Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 75, no. 4 (2016): 497-498. doi: 10.1525/jsah.2016.75.4.401

Schwartz, Frederic, Aldo Rossi, Vincent Joseph Scully, and Robert Venturi. Mother’s House: The Evolution of Vanna Venturi’s House in Chestnut Hill. New York: Rizzoli, 1992.

Scott Brown, Denise and Evelina Francia. “Learning from Africa: Denise Scott Brown talks about her early experiences to Evelina Francia,” The Zimbabwean Review (1995): 26-29.

Scott Brown, Denise. Having Words. London: AA Publications, 2010.

Scott Brown, Denise. “On Architectural Formalism & Social Concern,” Oppositions 5, (1976): 317-330.

Venturi Scott Brown & Associates, James Steele and Denise Scott Brown. Venturi Scott Brown & Associates: On Houses and Housing. London : Academy Editions ; New York : St. Martin’s Press, 1992.

Venturi, Robert, and Denise Scott Brown. Architecture as Signs and Systems: for a Mannerist Time. Cambridge, Mass. : Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2004.

Venturi, Robert, Denise Scott Brown, Steven Izenour. Learning From Las Vegas, Revised Edition. The MIT Press, 1977.

Venturi, Robert. Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture. New York : Museum of Modern Art ; Boston : distributed by New York Graphic Society, 1977.